Posted by rogerhollander in Ecuador, Health, Latin America, Uncategorized.

Tags: correa government, Ecuador, Ecuador Election, Ecuador Government, ecuador health, elections, galapagos, guillermo lasso, lenin moreno, lesser of evil, right wing, roger hollander, toruism

Reflection 1) For many years now my mantra has been: no more voting for the “lesser of evils.” I have dual U.S / Canadian citizenship, and in North American elections I vote Green, but with no illusions that if the Greens ever came to power they wouldn’t act any different than than the existing major parties. We’ve seen this time and time again where Social Democratic parties that call themselves Socialists form governments, they soon don’t smell any different than the others. Why is this inevitable? Because governments of capitalist democracies are basically there to protect the interests of capital over people; and the parties that win elections are basically tasked with administrating those interests.

Anything different would be, in fact, revolutionary. Fidel Castro understood this, which is why the Cuban Revolution didn’t devolve into wishy-washy social democracy.

So my Green vote is basically a protest vote.

But I digress. Back to the lesser of evils. As a Canadian / American it has become painfully obvious over many decades of observation and participation that when it comes to the big ticket items (military, finance, commerce, labor, etc.) there really is no substantial difference between the established parties. The Democrats in the U.S. and the New Democrats in Canada can only attempt to create the illusion that there is indeed such a difference.

Well I suppose mantras are made to be broken. Because the minute Trump was elected (no, the mini-second), which I never believed could happen, I was sorry I hadn’t voted for Clinton (whose policies on major issues I detest). The lesser of evils.

Which brings me to Ecuador. Sunday’s presidential election pitted the government supported candidate against a far right ex-banker (which the former won with a slim two percent advantage). While I do not support the Correa government’s actions with respect to environmental protection (its expansion of oil and metal extraction in sensitive areas) or its aggressive repression of protest; unlike any government before it, going back to the end of the dictatorship in 1979, it has invested heavily in health, education, housing and infrastructure and considerably reduced the level of poverty in the country.

On the other hand, the election of the ultra-right ex-banker Guillermo Lasso, who has ties with rightest governments across the hemisphere, the quasi-facist Opus Dei, and almost certainly our friendly CIA, would have signalled a return to the neo-Liberal economic policies so inimical to workers and the poor. The Lasso campaign played on the manufactured-in-the-USA fear that electing the government candidate would be turning Ecuador into Venezuela.

If I had a vote in Ecuador it would have been for the government candidate, so much for my mantra. The name of the president-elect, by the way, is Lenin Moreno (I would have preferred Vladimir, but you take what you can get).

(On a side note, you may remember that Wikileaks founder Julian Assange has been living for several years in the Ecuadorian Embassy in London, where he was given asylum by the Ecuadorian government. Well, Lasso had commented before the election that, if he won the presidency, he would cordially give Assange 30 days to leave the Embassy. Yesterday, upon receiving the election results, i.e., Lasso’s defeat, Assange made a statement calling for Lasso to cordially leave Ecuador in 30 days!)

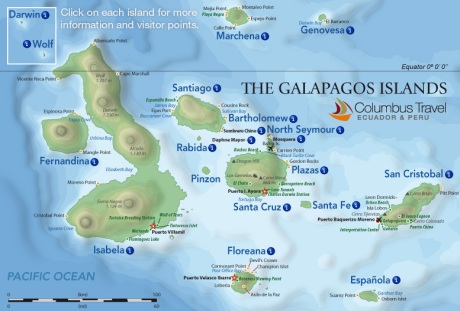

Reflection 2) My friend, David, who is a professor at a state university in the States, vacations every year in the Galapagos Islands, which is a province of Ecuador. This year, a week prior to his scheduled return home, he had a nasty bike accident and seriously injured his leg. He was carried back to his hotel, where he remained bed-ridden and unable to stand up. This was on the distant and less populated island of Isabella, which has a small under-supplied medical clinic and one doctor, who examined David and thought there might be a fracture. David was hoping that it was only severe ligament or muscle damage that would ease up in days so that he could rest up and return home on schedule.

On the Sunday prior to his scheduled departure on Tuesday, things still didn’t look good. The doctor suggested that they get him to the central island of Santa Cruz, where there is a hospital with an X-ray facility. The idea was that if there were no fracture, he could fly home Tuesday on schedule; but if it was serious, then he would probably have to remain in Ecuador for surgery.

On Monday, David flew to Santa Cruz, where his X-ray showed that he had indeed fractured his femur. However, in spite of this finding, David decided he would tough it out and fly home the following day loaded up with pain killers and have his operation in the States. This he did and is now resting post-surgery in a New Jersey hospital.

The point of my story? Here are the medical services that David received. The doctor who attended him on Isabella provided pain killers and spent an hour with him every day at his hotel. On Monday, an ambulance met him at the hotel and took him to the small Isabella airport, where he boarded for the island of Santa Cruz. At Santa Cruz and ambulance and a crew were waiting for him to take him to the hospital. When he decided, in spite of the X-ray result, to return home on Tuesday, he had to be taken from the hospital in Santa Cruz by boat to the Island of Baltra, where he would catch his flight to Guayaquil (Ecuador’s largest city) from whence he would take his American Airlines flight home to the States.

All these services: the doctor’s fees, the medication, the X-ray, the overnight hospital stay in Santa Cruz and the ambulance services were paid for by the government of Ecuador. And when David was informed that policy did not allow him to use an ambulance to get from Santa Cruz to his flight to Guayaquil because he was not being transported to an Ecuadorian hospital, David contacted his best friend and chess rival on the Galapagos, whose brother was the head of tourism there, it was arranged for an exception be made for him. Otherwise he could not have made it home.

This entire episode did not cost David a red cent!

Now I want you to imagine an Ecuadorian tourist to the United States experiencing a similar traumatic accident and what they would have gone through and what it would have cost them. And tell me, which country is the Banana Republic and which the “civilized” nation.

I experienced something similar in Cuba many years ago, but I will save that for another time.

Posted by rogerhollander in Ecuador, Latin America, Right Wing, Uncategorized.

Tags: alianza pais, amazon rainforest, democracy, Ecuador, Ecuador Election, ecuador oil, guillermo lasso, indigenous, kevin koenig, lenin moreno, Rafael Correa, roger hollander, yasuni

Roger’s note: This is a good, if limited, analysis of the Ecuadorian presidential run-off election that takes place this Sunday. In the first round of voting, the Government candidate, Lenin Moreno, needed 40% of the vote to avoid a second round. He won by a large amount against the rest of the field, but with 39.3% of the vote, he fell short of election.

Ten years of the Correa government has left the Ecuadorian left in shambles. The coalition that brought Correa to power — the Indigenous and campesino communities, the environmentalists, most of the social movements and labor unions — have been shut out and for the most part are considered “enemies” by Correa, and not only to him personally, but to the Ecuadorian state.

Watching the Indigenous organizations and most of the political lefts coming out in support of the Banker, Guillermo Lasso, is almost surreal. Lasso was the chief economic advisor (Superminister of Economy and Energy) to Jamil Mahuad, whose presidency was responsible for the infamous “banking holiday” in 1999 where thousands of Ecuadorians lost their life savings. Mahuad had to flee the country and landed at Harvard University’s Kennedy School, where he lectures on economics in spite of the fact that he is on INTERPOL’s wanted list (I am not making this up).

Candidate Lasso is connected to right wing governments throughout the region and to the alt-right Roman Catholic Opus Dei. Regardless of what he has told the Amazonian Indigenous in order to gain their support (a la Trump), his election would certainly mean a return to the pre-Correa belt-tightening neo-Liberal corruption that plagued the country for decades. For these reasons it is mind-boggling to see much of the left behind his candidacy.

Whether he wins or loses on Sunday, the Lasso phenomenon is another example of that notion that presidential elections in our so-called democracies do not give genuine options for social justice, that voters get fed up with existing governments and vote in whatever opposition option they are given, even those oppositions that are contrary to the self interest of those who vote them in (again, a la Trump).

Photo credit: Amazon Watch

By KEVIN KOENIG

All over the capital city of Quito and throughout the small towns in the countryside, campaign propaganda is everywhere. Posters choke telephone poles, flags hang from windows, awnings, and corner stores, entire houses are painted with the respective colors of Alianza PAIS – Ecuador’s governing party of the last ten years – and those of the opposition CREO party, which is running on the promise of change. This Sunday, Ecuadorians will take to the polls and vote again for president, and the stakes couldn’t be higher for the country’s Amazon rainforest and its indigenous inhabitants.

The April 2nd run-off election pits Guillermo Lasso, a right-wing former banker against the former vice president of the outgoing and controversial current president, Rafael Correa. It will be the first time in recent memory that Correa, the country’s longest-standing elected president, won’t be on the ballot. The Alianza PAIS ticket is led by both vice presidents who served under Correa: Lenin Moreno and Jorge Glas.

Ten years ago, Correa embarked on what he dubbed a “Citizens’ Revolution,” the largest expansion of public sector spending in the country’s history, which included investments in schools, hospitals, roads and other infrastructure development like port expansions and hydroelectric dams. The administration also greatly expanded subsidy programs for housing and monthly cash payments to the country’s poor.

But it has all come at a price. To implement these popular measures, and to maintain the national economy after being shut out of the finance world due to a debt default, Correa borrowed heavily from China, amassing loans for more than US $15 billion. But many of these loans must be paid in oil, committing the majority of the crude the country extracts to China through 2024. As oil prices have dropped, the quantity of oil needed to repay those loans has increased, essentially guaranteeing new oil drilling in Ecuador’s pristine, indigenous rainforest territories in the Amazon.

In other words, Correa made poverty reduction depend upon the exploitation of natural resources in one of the most ecologically and culturally important places on the planet. Correa once promised to “drill every drop of oil” in the Amazon, ignoring the ecological and cultural harm this would cause as well as the “resource curse” and likelihood of corruption (which has occurred in Ecuador) resulting from relying heavily on oil, gas, or mineral extraction as the mainstay of a country’s economy.

For his part, opposition leader Guillermo Lasso, a former banker from the port city of Guayaquil, promises a return to U.S.-aligned, right-wing policies and reliance upon traditional lending institutions like the IMF and World Bank. However, these very same institutions deserve much of the blame for the country’s historic natural resource dependence and austerity policies favoring export-led development and “free trade,” and these policies provoked a full-fledged banking collapse that forced the country to dollarize its economy in 2000. The backlash against these neoliberal policies by civil society and the indigenous movement led to the ousting of several presidents and a period of great political instability that set the stage for the ascendancy of Correa and his self-described “revolutionary” agenda.

Despite this history, in this campaign Lasso has endorsed the platform of CONFENAIE, the indigenous Amazonian confederation, which calls for an end to new oil and mining concessions, an amnesty for indigenous leaders currently facing charges of terrorism for leading anti-government protests, respect for the right to Free, Prior, Informed Consent (FPIC), and several other legal reforms affecting indigenous rights. This endorsement came after direct pressure on all the candidates from CONFENAIEand Yasunidos, an active environmental coalition that made a series of viral videos pressuring them to take strong stances on environmental protection and indigenous rights, especially in Yasuní National Park in the Amazon.

How he would implement such policies while also fulfilling his neoliberal campaign promises is an open question. If Ecuador elects him, it risks a return to past policies that were historically hostile to indigenous rights, including a likely re-opening to multinational companies that have run roughshod over the environment and human rights, as exemplified by the notorious Chevron-Texaco case.

Moreno, for the most part, has been largely silent on these issues, and so Ecuadorians and observers are left to expect a continuation of Correa’s extractivist policies.

In the first round, most Amazonian provinces chose Lasso, in a clear rejection of Correa’s efforts to expand oil and mining projects on indigenous lands, his crackdown on indigenous rights that has seen several leaders jailed and persecuted, and a state of emergency that lasted 60 days in the ongoing conflict between the Shuar, the government, and the Chinese mining conglomerate Explorcobres.

Nationally, the polls for the run-off election currently show a statistical dead heat, with Moreno at 52.4% and Lasso at 47.6%, with a margin of error of 3.4% and roughly 16% of voters undecided. Moreno’s lead is surprising, given that first-round voting split the conservative vote among several candidates who were predicted to coalesce around Lasso for the run-off. Each side has accused the other of dirty tricks: Lasso has accused the governing party of using state-run media and coffers to support its campaign, and Alianza PAIS has promoted allegations made public last week that Lasso has suspicious investments in several offshore businesses and properties. Each side has warned of possible fraud and both predict widespread protests after Sunday’s vote.

Regardless of who wins, the response to the escalated social conflicts over extractive industry projects, rollback of indigenous rights, and criminalization of civil society protest will be an early and pressing challenge for the incoming administration. Further oil and mineral development will only make the country’s economy more vulnerable to fluctuations in the world oil market, whose recent crash has Ecuador reeling. This, combined with the country’s extreme wealth disparity, means that further income from oil alone will not solve the problems of poverty in Ecuador. The country must create a diverse economy that addresses wealth inequality in order to reduce poverty.

How the new president responds will serve as an indicator of whether Ecuador can transition to a post-petroleum economy, save what remains of its pristine rainforests, and respect the rights of its indigenous inhabitants, or whether it will continue to see the Amazon and the indigenous peoples there as solely a source of short-term financial gain.

As Domingo Peas, an Achuar leader, told me today, “No matter who wins, our agenda is the same: a platform based on indigenous rights, territorial protection and defense, and solutions that maintain our forests intact, keep the oil in the ground, and show the world how frontline indigenous peoples have been protecting the sacred for millennia.”

The future of Ecuador’s Amazon – one of the most ecologically and culturally important places on the planet – hangs in the balance.

Posted by rogerhollander in Ecuador, Energy, Environment, Latin America, Uncategorized.

Tags: amazon, amazon rainforest, climate change, Ecuador, ecuador oil, environment, fossil fuel, global warming, Rafael Correa, rainforest, roger hollander

Roger’s note: Like all so-called leftist governments, with virtually no exceptions (Chile under Allende, and we saw what happened there), as stewards of the capitalist state they supposedly rule, it becomes expedient if not necessary, to move to the right, which means to accommodate the basic needs of capital. In the case of Correa’s Ecuador, the proposed destruction, ecological and cultural, of the rain-forest, is justified as an anti-poverty endeavor. In the face of falling oil prices, it is virtually a suicidal move (for the country, if not for the ruling elite). Exchanging US (IMF/World Bank) debt for Chinese debt will ensure the impoverization of the county in the long run. This while contributing to global warming and the possible of genocide of the self-imposed isolated indigenous tribes in the Ecuadorian Amazon.

Last week, the Ecuadorian government announced that it had begun constructing the first of a planned 276 wells, ten drilling platforms, and multiple related pipelines and production facilities in the ITT (Ishpingo-Tambococha-Tiputini) oil field, known as Block 43, which overlaps Yasuní National Park in Ecuador’s Amazon rainforest. Coupled with the recent signing of two new oil concessions on the southern border of Yasuní and plans to launch another oil lease auction for additional blocks in the country’s southern Amazon in late 2016, the slated drilling frenzy is part of a larger, aggressive move for new oil exploration as the country faces daunting oil-backed loan payments to China, its largest creditor.

Yasuní National Park is widely considered one of the most biodiverse places on the planet. It has more species per hectare of trees, shrubs, insects, birds, amphibians, and mammals than anywhere else in the world. It was designated a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve in 1989, and it is home to the Tagaeri-Taromenane, Ecuador’s last indigenous peoples living in voluntary isolation.

The controversial drilling plans were met with protest at the headquarters of state-run Petroamazonas’ Quito office, the company charged with developing the field. Ecuador averaged a spill per week between 2000 and 2010, which doesn’t bode well for drilling in a national park.

Despite touting the new perforation, the government is on the defensive, trying to downplay impact on the park. It points to the fact that the well site, Tiputini C, is technically outside of Yasuní’s limits. But, as the first wildcat well of hundreds planned, the government’s rhetoric is misleading at best.

Correa also boldly claimed that drilling in the adjacent Block 31 concession was not inside the boundary of Yasuní National Park, which was followed by a press conference from Environmental Minister Daniel Ortega who reiterated that claim. But activists are crying foul.

“The government is lying,” said Patricio Chavez, a member of Yasunídos, a national collective dedicated to defend Yasuní National Park. “They have no idea what they’re talking about. We’re not sure whether they make these statements because they honestly don’t know their own country or they’re trying to intentionally confuse people.”

In fact, Block 31 is in the heart of Yasuní National Park, with the two oil fields clearly in the middle of the block. The Ministry of Hydrocarbons’ own map shows a pipeline extending to the Apaika field – in the middle of the block and the heart of the park.

Conveniently for the government, though, both Block 31 and Block 43 are highly militarized and entrance by the public is forbidden. But satellite images and investigative undercover missions into the area not only show oil activity underway but also the construction of illegal roads in violation of the environmental license.

But don’t be fooled. In fact, there are currently eight oil blocks that overlap Yasuní National Park, which calls into question the relevance of its “national park” status with so much drilling either underway or planned.

“The park and its indigenous peoples are under siege,” said Leo Cerda, a Kichwa youth leader and Amazon Watch Field Coordinator. “If this is how a national park is treated, imagine what drilling in an ‘unprotected’ area looks like.”

Expanding drilling activity in the park has left the nomadic Tagaeri-Taromenane virtually surrounded. Recent conflicts between the two clans and their Waorani relatives has led to several killings and other inter-ethnic violence. While there are different theories as to the roots of the confrontations, dwindling territory, scarce resources, noise from oil activity, and encroachment by outsiders are all likely factors. Regardless, so much pressure on the park and its inhabitants is having predictable and tragic consequences.

The drilling plans have been a flashpoint since 2013 when President Rafael Correa pulled the plug on the Yasuní-ITT initiative, a proposal to permanently keep the ITT fields – an estimated 920 million barrels of oil – in the ground in exchange for international contributions equaling half of Ecuador’s forfeited revenue.

The initiative failed to attract funds, in part because Annex I countries were unwilling to contribute to an untested supply-side proposal to keep fossil fuels in the ground instead of more traditional demand-side regulations and carbon offsets. Essentially, northern countries – the most responsible for climate change – were unwilling to cough up cash to protect one of the world’s most important places if they weren’t going to get anything in exchange.

Scientists now agree that we need to keep at least 80 percent of all fossil fuels in the ground to avoid a catastrophic 1.5℃ rise in global temperature, so Ecuador’s proposal was apparently ahead of its time. The world dropped the ball, but the blame for the initiative’s stillbirth is shared.

The Correa administration mismanaged the initiative from the outset. It took several years to establish a trust fund where people and governments could contribute. But more detrimental was the administration’s simultaneous tender of multiple oil blocks in the country’s southern Amazon. Why pay to keep oil in the ground in one place if the host country government merely opens up new areas to compensate for lost revenue? Correa’s have-your-cake-and-eat-it-too politics were not very convincing to potential donors.

Public outrage and protest met Correa’s unilateral decision to scrap the initiative. A six-month national mobilization to force a ballot initiative on drilling plans garnered over 700,000 signatures, far more than the required 400,000. But almost half were nullified by Ecuador National Election Council in a process littered with secrecy and fraud.

“When the Yasuní-ITT initiative was launched, the idea was that leaving the oil in the ground would help address environmental and economic problems on the local, national, and global level,” said Esperanza Martinez, President of Ecuador’s Accion Ecologica and founder of the Oilwatch network. “The abandonment of the initiative has come with an aggressive push on Yasuní – on its borders to the north, south, east, and west. But the decision to drill now comes at a time when the world is talking about breaking free of fossil fuel dependence and agreeing on targets to avoid the rise of global temperature.”

Martinez continued, “It makes no sense to drill now – at great biological and cultural risk – when economically Ecuador is losing money with each barrel extracted. There is no justification that drilling in Yasuní is in the economic interest of the country.”

Indeed, it costs Ecuador $39 to produce a barrel of oil. But current market price for its two types of crude are in the low $30s, so Ecuador is losing money on each barrel being pulled from the ground. And when the aboveground ecosystem is one of the most important in the world and drilling activities threaten the ethnocide of isolated peoples, drilling at a loss is bewildering. Of course, there is no price per barrel that would justify drilling in such an environmentally pristine and culturally sensitive area with the extinction of a people at risk.

A major factor in Ecuador’s drive to expand drilling in Yasuní and beyond, despite the current oil market context of abundant and cheap oil, is the country’s outstanding debt to China. According to a Boston University/Inter-American Dialogue Database, Ecuador has obtained 11 loans, totalling about $15.2 billion, much of which must be paid back with petroleum.

But the move into Yasuní coincides with an equally aggressive push to open new areas south of Yasuní in a large, roadless pristine swath of forest that extends out to the Peruvian border.

Two blocks, 79 and 83, were recently concessioned, and drilling deals were signed with Andes Petroleum, a Chinese state-run firm. Faced with adamant opposition from both the Sápara and Kichwa peoples whose legally-titled territory overlaps these oil blocks, the government has sought to divide the indigenous communities.

Speaking at an Inter-American Human Rights Commission hearing on Monday, Franco Viteri, President of CONFENAIE (Confederation of Amazonian Indigenous Peoples of Ecuador), described efforts of the government to divide the legitimate indigenous organizations with the aim of circumventing resistance to resource extraction and advancing Andes Petroleum’s drilling plans.

“The objective of the government is to create acceptance – or the appearance of acceptance – of resource extraction. That’s what the government wants because we are resisting resource extraction projects like oil and mining throughout the Amazon region.”

Manari Ushigua, President of the Sápara federation, whose territory is almost totally engulfed by Blocks 79 and 83, also addressed the government’s intentions.

“The goal of the Ecuadorian government is to divide us and open our land to oil extraction. We live in peace, with the natural world, with our spirits. But our elders are few. We are on the verge of extinction.”

The government has also announced plans to launch a new oil licensing round in late 2016 which would sell off several other oil blocks in Ecuador’s southern Amazon. However, the last auction, known as the 11th Round, was a widely recognized failure. Offering thirteen blocks, the government only received four bids, two of those from the same company – Andes. Clearly, the Chinese state-run firm wants to make sure that its sole shareholder, the Chinese government, gets paid back for its generous lending to Ecuador. And because the payments are in oil, it explains why Ecuador is forced to expand drilling, even if it’s at a loss. China can then turn around and sell the barrels of oil in the open market for a substantial profit.

Ecuador’s new oil boom is ill-timed. While several years ago the country was the vanguard of what is now a worldwide movement to #keepitintheground, Correa’s “Drill, baby, drill!” policies place its frontier forests and indigenous peoples at great risk. As I’ve written before, Ecuador’s pipe dream of prosperity from perforating wells like ITT have failed to pan out, instead trapping the country in a downward spiral of debt, dependency, and environmental destruction.

However, the movement to #keepitintheground in Ecuador is growing. Ecuador’s 11th Oil Round failed mostly because communities on the ground vowed resistance and indigenous leaders traveled to every oil expo at which the government sought to sell its Amazon oil blocks to the highest bidders – including Quito, Houston, Paris, and Calgary – and let any interested company or investor know that their lands were not for sale. Indigenous peoples across Ecuador’s Amazon have again vowed to keep the companies out and they are asking for our solidarity. Let’s join them!

September 4, 2015

Posted by rogerhollander in Ecuador, First Nations, Latin America.

Tags: Alberto Acosta, CONAIE, correismo, Ecuador, ecuador indigenous, ecuador indigenous protest, ecuador neoliberalism, ecuador protest, Ecuadorian left, guillermo lasso, jaime nebot, mauricio rodas, Rafael Correa, roger hollander

Left and indigenous forces in Ecuador are attempting to create an alternative to both Rafael Correa and the Right.

Jacobin

30th August 2015

On August 13, an indigenous march and people’s strike converged on the Andean city of Quito, Ecuador’s political center. The march was coordinated principally by the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE), and began on August 2 in Zamora Chinchipe, passing through Loja, Azuay, Cañar, Chimborazo, Tungurahua, Cotopaxi, and Salcedo before arriving in the capital. Demands emanating from the different sectors of urban and rural groups supporting the initiative were diverse, and sometimes contradictory.

But Alberto Acosta, at least, sees a certain clarity in the tangle of ideas and demands. Acosta was the presidential candidate for the Plurinational Unity of Lefts in the 2013 general elections. An economist by profession, he was the minister of mines and energy and president of the Constituent Assembly in the opening years of the Correa government. After the assembly ended, he and Correa parted ways, but Acosta remains an important shaper of opinion in the country. In the lead-up to August 13, he maintained that, contrary to popular assessments, there was a discernible political core to the protesters’ demands.

According to Acosta, the people in the streets are opposed to any constitutional changes that will allow indefinite reelection of the president and demand an end to the ongoing criminalization of social protest. They are outraged by a new agrarian reform initiative that will displace peasants and advance the interests of agro-business, and they are lined up against the expansion of mega-mines and their nightmarish socio-ecological implications.

The demonstrators are defending workers’ rights to organize and strike, elemental freedoms limited in the Labor Code introduced in April this year. They are aligned against oil exploitation in Yasuní, one of the most biodiverse areas in the world, and a zone that Correa promised to protect and then abandoned. Finally, the popular organizations are opposed to the neoliberal free trade agreement Ecuador signed with the European Union that erodes the country’s sovereignty. These overlapping concerns, according to Acosta, overshadow other divisions on the Left.

A Day in the Streets of Quito

Despite this shared mission, walking through the different sections of the August 13 march, it was difficult to miss the contest for hegemony unfolding within the opposition. Left-wing unions called for dignified wages and the right to strike, while socialist feminists chanted slogans against Correa’s Opus Dei-inflected “family plan” and anticapitalist environmental groups marched against extractivism — particularly the expansion of the mining, oil, and agro-industrial frontiers.

Alongside these groups were social-democratic and revolutionary socialist and anarchist collectives, some with significant strength and long organizational histories, others little more than affinity groups. These eclectic expressions of a Left — broadly conceived — dominated the streets in numbers and political sophistication, but they have yet to cohere into a unified left bloc, independent of Correa.

CONAIE issued a public manifesto after a three-day conference in February, outlining demands that are clearly distinguishable from the politics of the Right — contrary to the suggestions of state officials — and reiterate longstanding aims of the indigenous movement.

It’s patently clear that Correa’s Manichean worldview, in which the population is with the government or with the Right, obscures more than it reveals. Still, the social bases, potential or realized, of the myriad faces of the right-wing opposition — Guillermo Lasso, the largest shareholder in the Bank of Guayaquil and 2013 presidential candidate for the Right; Jaime Nebot, the conservative mayor of Guayaquil; and Mauricio Rodas, the mayor of Quito — were also visible in the avenues and byways of Quito.

This politics found material expression in middle-class banners defending families and freedom, and audible resonance in the chanted echoes of “Down with the dictator!” President Correa points to the large demonstrations of last June against taxes on inheritance and capital gains as evidence that this Right is a real and imminent threat to stability.

The immediate battle lines of the demonstration — on the Left and Right alike — were delineated by the various participants’ desires to demonstrate social power in the extra-parliamentary domain, but anxious anticipation of the 2017 general elections weighed on every element of the day’s events. No one knows if Correa will amend the constitution and run a third time as the candidate for PAIS Alliance (AP), the party in power since 2007, and under Correa’s leadership since its inception.

Golpe Blando?

During the commodities boom, life for Ecuador’s poor improved. According to official figures — which use $2.63 per day as the baseline — poverty in Ecuador declined from 37.6 percent in 2006 to 22.5 percent in 2014, while inequality income (measured by the Gini index) also improved.

In that economic context, Correa could maintain his popularity through a fluctuating amalgam of co-optive measures and targeted retaliation vis-à-vis the principal social movements, especially the indigenous movement, which is fighting a two-pronged battle centered on socio-ecological conflicts around mining and the integrity of indigenous territories. Under charges of “terrorism and sabotage,” several nonviolent indigenous leaders have been jailed and are serving punitive sentences for activities like blocking roads or preventing mining companies from gaining access to their (ever-expanding) concessions throughout the country.

But recently, amid an extended rut in oil prices and looming austerity measures, the Correa administration has suffered significant declines in popularity. According to the indispensable conjunctural reports regularly published by sociologist Pablo Ospina Peralta, polling data show the president has lost between ten and twenty points in popularity over the last few months.

In the face of growing discontent, the Correa administration has responded defensively by framing the demonstrations as either intentionally, or naively, playing into the hands of the domestic right and imperialism, reinforcing the destabilization of the country, and laying the groundwork for the Right to enact a golpe blando, or soft coup.

One AP congressperson, María Augusta, casually told the media that the CIA financed the indigenous march, although she offered no evidence for this claim. Correa himself blames indigenous and labor “elites” for the demonstration, arguing they have no sense of the interests and sentiments of their rank-and-file bases.

Activism has become sedition, and left-wing dissent betrayal of the country. Two prominent indigenous leaders were arrested at the end of the day on August 13 and roughed up by police: Carlos Pérez Guartambel, of the Andean indigenous organization ECUARUNARI, and Salvador Quishpe, the prefect of Zamora Chinchipe. Manuela Picq, a French and Brazilian academic and journalist who has lived in Ecuador for eight years on a cultural-exchange visa and is Pérez Guartambel’s partner, was also arrested and threatened with deportation.

Vying for Hegemony

Just as the right-wing anti-tax protests in June were a sign of the political fragility ofCorreísmo in the medium term, the weighty presence of the Left in the recent protests suggests that the popular sectors sense a change in the balance of forces as well. “What is at the center of the national debate is the exit from Correísmo,” Acosta explains. “How, with whom, towards what, and on what terms.”

Yet, as Alejandra Santillana Ortíz recently suggested, it can be misleading to map the trajectory of dissent leading to the present moment using proximate catalysts, like the falling price of oil. Ruptures between social movements and the state began to surface in earnest as far back as 2009 and have intensified measurably over the last three years. Their culmination in the strike on Quito is at least as much a question of this medium durée as it is the response to political-economic developments of the last couple of months.

Sociologist Mario Unda’s recent snapshot comparison of the country’s principal socio-political lines of demarcation in 2007 and 2013 (the first year of the first and second administrations of Correa, respectively) echoes this perspective. For Unda, the outset of the first Correa administration conflict was overdetermined in many ways, by the Right’s fear of Correa’s potential radicalism and the Left’s hope for the same.

Conflict gravitated around the political-institutional terrain of the state, with the Right still retaining control of the National Assembly and the Supreme Electoral Tribunal. Alongside this institutional competition with the Right, big private media corporations lined up against Correa, increasingly playing the role of conservative opposition, as the traditional parties of the Right imploded into irrelevance. The principal business confederations in the country also adopted an extremely confrontational stance in the face of the new government.

At the same time, even in 2007 it was possible to identify certain lines of conflict between the AP government and popular movements and sectors. Some of these were marginal and localized — disputes over rural and urban service provision, labor disputes, pension disputes, and so on. However, in the countryside the indigenous movement was already being drawn into battles with the state and multinational capital on the extractive fronts of mining, oil, water, hydroelectricity, and agro-industry.

Far from marginalia, these issues proved central to Correa’s development model in the years to come. In 2009, for example, a pair of laws on mining and water sparked the largest protests witnessed in the first three years of the Correa administration.

The mining law facilitated the rapid extension of favorable concessions to multinational mining companies throughout the length and breadth of the country, while the water law privatized access to communal water sources (crucial legislation for large-scale private mining initiatives), limited community and indigenous self-management of water resources, and relaxed regulations on water contamination. With mineral prices soaring on the international market and oil reserves diminishing in the national territory, Correa staked the country’s future on the gold under the soil.

By comparison to 2007, the divisions were much clearer in 2013. The scene was determined not by the axis of right-wing contestation with the government, but rather by the government’s growing disputes with popular movements and their historic allies. There were conflicts with the bourgeoisie to be sure, but these disagreements were only with certain sectors of the elite, and face-offs with capital no longer accurately captured the determining dynamics of the terrain.

Instead, the Correa government’s principal enemy had become the indigenous movement and “infantile” environmentalists, and consequently, the government threw all its coercive and co-optive powers in that direction. At the same time, Correa sharpened his relations with public-sector workers, most notoriously laying off thousands through obligatory redundancies.

High schools — students and teachers — were another live field of contention, as the government tried to ram through “meritocratic” reforms in the educational sector. All the while, criminalization and control of social protest and independent organizing was a primary concern of the government.

Ideologically as well, the Right had taken on novel forms by 2013, relative to their collective demeanor in 2007. Sections of the traditional right continued to battle for a purist retention of neoliberal axioms, but there were also new experiments — like Creando Oportunidades and the Sociedad Unida Más Acción — that sought to present a public image of moderation and modernity, appropriating much of the language of the Correa administration for itself.

The economic organizations of the bourgeoisie were also developing in interesting directions. The confrontational disposition of business confederations was largely eclipsed by 2013, and most federations had elected new leaderships whose mandates were to negotiate and reach agreement with a government seen to be far more flexible than originally anticipated. The negotiation hypothesis of the Right paid dividends in the creation of a new ministry of foreign trade, and the signing of the Ecuador-EU free trade agreement, which had the enthusiastic backing of all the big capitals.

Unda argues that the dispute between the government and the bourgeoisie had metamorphosed into an internal dispute, and while control of the state apparatus was still a domain of contestation, the field of consensus on capitalist modernization — a fundamentally shared vision of society and development — defined the broader politico-economic backdrop.

Of course, this did not mean the obsolescence of sectional and conjunctural conflict, but it did mean the bourgeois-state axis of conflict had been eclipsed by that of the state–popular movement. The disputes with business and the Right were disputes over control of the same societal project, whereas battle lines between popular movements and the state were drawn over distinct visions of society, development, and the future.

Latin America’s Passive Revolution

Massimo Modonesi’s reading of Antonio Gramsci’s “passive revolution” is useful for making sense of the trajectories of progressive governments in South America over the last ten to fifteen years. In Modonessi’s interpretation of Gramsci, passive revolution encompasses an unequal and dialectical combination of two tendencies simultaneously present in a single epoch — one of restoration of the old order and the other of revolution, one of preservation and the other of transformation.

The two tendencies coexist in tandem, but it is possible to decipher one tendency that ultimately determines or characterizes the process or cycle of a given epoch. The transformative features of a passive revolution mark a distinct set of changes from the preceding period, but those changes ultimately guarantee the stability of the fundamental relations of domination, even while these assume novel political forms.

At the same time, the specific class content of passive revolutions can vary within certain limits — that is to say, the different degrees to which particular components of popular demands are incorporated (the transformative tendency) within a matrix that ultimately sustains the fundamental relations of domination (the restorative tendency).

Passive revolutions involve neither total restoration of the old order, the full reenactment of the status quo, nor radical revolution. Instead, they involve a dialectic of revolution/restoration, transformation/preservation.

Capacities for social mobilization from below in early stages are contained or coopted — or selectively repressed — while the political initiative of sections of the dominant classes is restored. In the process, a new mode of domination is established that is capable of enacting conservative reforms masked in the language of earlier impulses emerging from below, and thus achieving a passive consensus of the dominated classes.

Rather than an instantaneous restoration, under passive revolution there is a molecular change in the balance of forces that gradually drains the capacities for self-organization and self-activity from below through cooptation, encouraging demobilization and guaranteeing passive acceptance of the new order.

In the context of Ecuador, Agustín Cueva’s Marxist theorization of impasse in the 1970s parallels Modonessi’s passive revolution most closely. There have been recurring moments in Ecuadorian history where the intensity of the horizontal, intra-capital conflicts, in combination with vertical contests between the ruling and popular classes, was simply too much for the existing form of domination to bear. As politicians sought new and more stable forms of domination, instability reigned in the interregnum, until an impasse was reached.

Overcoming such impasses, as sociologist Francisco Muñoz Jaramillo points out, has been the work of populists, in Ecuadorian history, of Caesars and Bonapartes. Think of the left-military government of Guillermo Rodríguez Lara (1972–75) or that of left-populist Jaime Roldós (1979–1982), which took up the ideological mantle of newly emergent bourgeois layers against some of the interests of traditional oligarchs and incorporated the popular sectors through corporatist techniques of sectional negotiation and bargaining.

Between 1982 and 2006, the dominant classes of the country attempted to introduce neoliberal restructuring through a variety of channels. It was a deeply unstable period, reaching an apex in the 1999 financial crisis, followed by a series of mobilizations that threw out various heads of state in succession before their mandate was completed.

The orthodox neoliberal governments of León Febres Cordero (1984–88), Sixto Durán Ballén (1992–96), and Jamil Mahuad (1998–2000) tried and failed, in many ways, to carry out far-reaching structural adjustment programs, giving birth to right-wing populist experiments, such as Abadalá Bucaram (1996–97) and Lucio Gutiérrez (2003–5).

Accused of embezzlement and corruption, mass protests succeeded in forcing Bucaram’s impeachment. A military man, Gutiérrez, after participating in a short-lived coup against Mahuad in 2000, ran on a left ticket in the 2002 presidential elections, but governed from the right, and thus was overthrown as well.

Correa and the Left

These were two decades, then, of a neoliberal variant of Cueva’s recurring impasse. Correa calmed the storm and restored profits in sectors like banking, mining, oil, and agro-industry, and has simultaneously coopted or crushed most independent social movement activity.

Rhetorically, the government has employed vague ideologies, from buen vivir (an indigenous conception of “living well”) in the beginning of the administration, to the techno-fetishism that has dominated the last several years (best exemplified in theYachay Tech university debacle, and some dystopic model cities in the Amazon, as the excellent research team at the local think tank CENEDET has pointed out).

At the end of the day, Correa has been functional to capital. However, this isn’t the same as saying he is capital’s first choice — like all his populist predecessors, Correa is expendable. With the price of oil falling, capital is scrambling to collect what’s available and regain more direct control of the state. It’s an uncertain period ahead, and the sentiment on the Right is that Correa should go. A recent piece in the Economistcaptures this nicely, essentially thanking him for his service while showing him the door:

Mr. Correa faces a choice . . . He could persist in his bid for permanent power and risk being kicked out by the street, like his predecessors. Or he could swallow his pride, stabilize the economy and drop his re-election bid. He would then go down in history as one of Ecuador’s most successful presidents.

The various forces of the Left, broadly defined, are meanwhile trying to rebuild and regain initiative and forge the bases of a societal project that is a genuine alternative to both Correa and the Right. But the Left is starting from a point of weakness and disarticulation, and the present ideological and political landscape could scarcely be more complicated.

Original article: https://www.jacobinmag.com/2015/08/correa-pink-tide-gramsci-peoples-march/

|

|

Posted by rogerhollander in Ecuador, First Nations, Latin America.

Tags: Alberto Acosta, Ecuador, ecuador indigenous, ecuador indigenous protest, ecuador opposition, gerard coffey, Rafael Correa, roger hollander, yasuni

August 27 2015

One of the things the 2013 presidential candidate Alberto Acosta remarked on after the left’s comprehensive defeat, was that the political stability Rafael Correa brought to the country after a decade of chaos had been a major factors in his victory at the polls. People had appreciated it more than was evident at the time. The thought comes to mind now, in the wake of August’s major anti-government demonstrations that in all probability are only precursor of an even greater test of strength in the next few months. The Pax Correana may be finally be coming to an end.

The president rather unsurprisingly dismissed the protests as the work of a few, adding insults for good measure, as is his wont. Few they were not however, although diverse they certainly were. And after days and nights of tear gas and anti Correa chants, of arrests, violence and the de facto deportation of an indigenous leader’s partner[i], a respectable number were still protesting a week later. Tenacity was certainly not lacking. Although the marches and demonstrations may have come to an end, this is not the end, the protestors will be back in mid-September. Round two promises more of the same.

The government’s customary confrontational attitude exacerbated everything, but then no one expected Rafael Correa to lie down and be rolled over; the South American Margaret Thatcher, though clearly with another agenda, is not for turning. But Margaret Thatcher was finally turned, by her own people. Decisiveness and strength may be useful in a politician, cutting through Gordian knots is a talent, but limits there are, and in the end strength can too easily become weakness, as Thatcher found out. The hope is that the comparison between the two leaders will not be lost on any government official or legislator that cares to think about it. Unfortunately, few likely will.

A major difficulty is the country’s political structure. The indigenous populations, there are a number in the country, have been denigrated and ‘repressed’ since the time Columbus stumbled into the Caribbean, and the long fight for recognition and equality is not yet in sight. Nor has racism disappeared and can be counted on to erupt when the ‘indios’ claim their rights, in particular hen the government denigrates them in the name of governing for the great majority. At the same time, trying as Rafael Correa has to impose the evidently unsuccessful French model of the supposed equality of all – we are all Citoyens in Correa’s Ecuador – was never likely to succeed in the multicultural world of the Andes. One of the indigenous groups’ deepest fears is disappearance, a slow melting away into an amorphous population that might acknowledged their (its) past but not their present or future.

Anything that may consequently hasten that evaporation – loss of control over territory due to large extractive projects such as mining and oil, loss of influence over water supply as a result of recently passed legislation, added to lack of support for the small scale farming on which many, and the internal market, still depend – will as a result be fiercely resisted. Understanding that man does not live by bread alone is crucial. In addition, we have the President’s tendency to insult anyone getting in his way, and as the group with the most to organize against him, the ‘indios’, have consequently received special attention. Given their history it is hardly surprising that derision is not appreciated.

So the indigenous people have legitimate claims, but no way to make them heard, or rather have them resolved. As a minority, representative democracy does not work in their favour, but as a special case, and few would care to deny that this they are, they deserve better. They know it and so do we; so when they say that building roads, schools and hospitals is not enough, we should be listening. If we do not, if the government does not, because as the President likes to repeat ad nauseum, he has an electoral mandate, then the obvious answer for indigenous groups is to use whatever tools they may have at their disposal: blocking roads being one of them.

Blocking roads is of course prohibited, and to emphasise the point President Correa stated the obvious: that roads would be cleared, more or less ‘at any cost’. Fortunately ‘at any cost’ did not come to pass, but costs in the form of violence and arrests came quickly enough. The use of the police and military to control the population in times of trouble may be necessary, the government can hardly be expected to hand over control to whoever cares to challenge it, but the cost will be high, both in terms of people injured and credibility lost. And all sides know it[ii].

The pattern is familiar: the police attempt to dislodge the protestors who in turn resist, at times violently, the police, hardly known for being gentle in these kinds of situations, react with even greater violence, and so on, and so on… the protestors finally lose and the road is cleared. No one accepts any responsibility, not police, who have their own injured to show for their efforts, or the government, which claims that it is just trying to maintain order and that the police are heroes, or even the indigenous groups, whose protest may be legitimate, but whose tactics may be questionable unless the idea is to use the victims of police violence as evidence of the state’s lack of legitimacy.

Whatever the case may be, the outcome of the latest battles will not bring peace. This war is not over. Neither the violence, nor the arrests, nor the confrontational rhetoric, nor the clumsily belligerent threat of legal action against the head of the country’s most important indigenous organization will be enough to stop the next march, or the one after that. In all likelihood they will have the opposite effect. And there is also the small matter of the debate in the National Assembly over whether to allow Rafael Correa to be indefinitely re-elected[iii]. Planned for December, insistence on passing the measure without a national plebiscite (according to the polls eighty percent or more are in favour of being consulted) will bring a lot more people onto the street: the indigenous groups, the right, the left, the center, the good, the bad and the ugly…

The indigenous agenda is not the only one of course; there are many grievances – the use of the justice system to hound political enemies; the setting up of government sponsored social organisations to divide the opposition; the decision to drill for oil in Yasuní National Park; the imposition of Catholic values on a constitutionally lay state; the president’s bellicose style, etc. etc. – but it is the central theme around which the others will likely gel. Even the right will support it to some degree, until it regains power.

That all things pass is not at issue, the real question is the timing. Rafael Correa’s time as President has not yet been defined: he might survive to run again, he might even win, but the end of his tenure and of the region’s ‘progressive’ governments seems to be drawing closer; only the faithful or those with vested interests would argue the contrary. On the other hand, his reign has not been a failure; many good things have happened over the last eight years. But added to the erosion of his personal credibility, the political and economic atmosphere is not what it was in 2005 when he first ran for President, witness the situations in Brasil and Venezuela. Ecuador is not Venezuela, not yet at any rate, and no major corruption scandal has stained the government as in Brasil, not yet at any rate, but as in that country the rapidly deteriorating economic situation will almost inevitably increase disillusion with ‘progressive’ leaders, and consequently add to the President’s woes.

The only bright spot for Rafael Correa and his supporters is that until now no credible opponent has appeared, certainly not on the left, which has no real electoral structure and appears to be betting everything on the protests. The tactic would appear to be somewhat shortsighted as despite the dire economic situation[iv] people want to believe in something, in the possibility of a brighter future, however defined. Optimism is the opiate of the people as Milan Kundera once concluded and Rafael Correa is if nothing else the master of optimism, a sort of Ecuadorian pied piper if you will, whose approval rating is still at a healthy fifty percent. Correa seems far from finished, but then again the same appeared to be true in Brasil before Dilma Rousseff ran for reelection; now she hangs on for dear life and makes deals with the neoliberal right. Despite the wisdom of the old adage, previously disdained opposition candidates have a habit of becoming credible in the face of already known and increasingly unpopular devils.

[i] Manuela Picq a Franco-Brasilian academic who has also written for the Al Jazeera English Network, is the partner of Carlos Pérez Guartambel, the President of Ecuarunari, the country’s principal Kichwa organization. She was arrested during the protests, was about to have her visa rescinded when she decided to leave voluntarily. She is unlikely to be allowed back in.

[ii] It has been suggested that infiltrators were used by the government to provoke attacks on the police and discredit a pacific protest.

[iii] According to the country’s reigning Constitution, approved in 2009, the President can only be re-elected once. Amending the Constitution can be done in two ways: by popular vote if it the changes are deemed to alter the fundamental nature of the state, or if not, by a two thirds parliamentary majority, which Correa’s party has.

[iv] Since 2000 Ecuador’s currency is the US dollar, which presently stands at an almost historic high against other currencies. Without the capacity to devalue the country’s exports are suffering, at the same time that the price of oil, the country’s major export has dropped below $40 a barrel. The president recently suggested that Ecuador’s income from oil would amount to no more than US$40 million this year.

|

Posted by rogerhollander in Criminal Justice, Ecuador, Environment, Imperialism, Latin America, Whistle-blowing.

Tags: amazon watch, chevron, chevron ecuador, chevron oil spill, Ecuador, ecuadorian amazon, environment, lauren mccauley, oil spill, roger hollander, whistleblower

Roger’s note: who is more likely to face legal consequences: Chevron or the whistleblower? And how does this relate to our capitalist political/economic reality where the distinction between corporate wealth and government becomes smaller by the day?

Published on

Wednesday, April 08, 2015

by

Videos sent to Amazon Watch described as ‘a true treasure trove of Chevron misdeeds and corporate malfeasance’

‘The videos are a true treasure trove of Chevron misdeeds and corporate malfeasance,’ said Kevin Koenig of Amazon Watch. ‘And, ironically, Chevron itself proved their authenticity.’ (Screenshot from The Chevron Tapes)

In what is being described as “smoking gun evidence” of Chevron’s complete guilt and corruption in the case of an oil spill in the Ecuadorian Amazon, internal videos leaked to an environmental watchdog show company technicians finding and then mocking the extensive oil contamination in areas that the oil giant told courts had been restored.

A Chevron whistleblower reportedly sent “dozens of DVDs” to U.S.-based Amazon Watch with a handwritten note stating: “I hope this is useful for you in your trial against Texaco/Chevron. [signed] A Friend from Chevron.”

The videos were all titled “pre-inspection” with dates and places of the former oil production sites where judicially-supervised inspections were set to take place. The footage was recorded by Chevron during an earlier visit to the site to determine where clean samples could be taken.

According to Amazon Watch’s description of the tapes:

Chevron employees and consultants can be heard joking about clearly visible pollution in soil samples being pulled out of the ground from waste pits that Chevron testified before both U.S. and Ecuadorian courts had been remediated in the mid-1990s.

In a March 2005 video, a Chevron employee, named Rene, taunts a company consultant, named Dave, at well site Shushufindi 21: “… you keep finding oil in places where it shouldn’t have been…. Nice job, Dave. Give you one simple task: Don’t find petroleum.”

In other videos, local villagers interviewed about the pollution recount how “that company” never actually cleaned the waste pits and instead covered them with dirt to try to hide the contamination.

“This is smoking gun evidence that shows Chevron hands are dirty—first for contaminating the region, and then for manipulating and hiding critical evidence,” said Paul Paz y Miño, Amazon Watch’s director of outreach.

In February 2011, an Ecuadorian court found the oil giant guilty and ordered Chevron to pay $8 billion in environmental damages, a ruling the company called “illegitimate” and vowed to fight. In 2014, a U.S. federal court judge sided with Chevron and threw out that ruling, arguing that it was obtained through “corrupt means.” On April 20, a federal appellate court in Manhattan will hear oral argument in the appeal of those charges.

“While its technicians were engaging in fraud in the field, Chevron’s management team was launching a campaign to demonize the Ecuadorians and their lawyers as a way to distract attention from the company’s reckless misconduct,” Paz y Miño added.

Chevron never turned over any of the secret videos to the Ecuador court conducting the trial. Nor did the company submit its pre-inspection sampling results to the court.

In a blog post on Wednesday, Amazon Watch Ecuador program coordinator Kevin Koenig explains how, after receiving the tapes, his organization turned them over to the legal team representing the affected Indigenous and farmer communities.

“The videos are a true treasure trove of Chevron misdeeds and corporate malfeasance,” he writes. “And, ironically, Chevron itself proved their authenticity.”

Koenig continues:

When the plaintiffs’ lawyers tried to use the videos in court to cross-examine a Chevron “scientist”, the company objected.

A letter sent by Chevron’s legal firm Gibson Dunn to counsel for the communities states, “These videos are Chevron’s property, and are confidential documents and/or protected litigation work product. Chevron demands that you provide detailed information about how your firm acquired these videos and your actions with respect to them… In addition to providing this information, Chevron demands that you promptly return the improperly obtained videos and all copies of them by sending them to my attention at the above address.”

Chevron is now free to view them on YouTube.

“These explosive videos confirm what the Ecuadorian Supreme Court has found after reviewing the evidence: that Chevron has lied for years about its pollution problem in Ecuador,” Koenig added.

Chevron has admitted to dumping nearly 16 billion gallons of toxic oil drilling wastewater into rivers and streams relied upon by thousands of people for drinking, bathing, and fishing. The company also abandoned hundreds of unlined, open waste pits filled with crude, sludge, and oil drilling chemicals throughout the Ecuadorian Amazon.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 License

Posted by rogerhollander in Ecuador, Energy, Environment, First Nations, Latin America.

Tags: Ecuador, ecuadorian amazon, environment, indigenous, oil exploitation, oil exploration, roger hollander, yasuni

YASunidos is an Ecuadorian youth movement which collected 750 000 signatures to prevent oil drilling in Yasuní national park in Ecuador.

They have been nominated for “The Human Rights Tulip” award, a prize worth €100 000.

This money could be used perfectly to further expand and deepen their campaign to save the Yasuní national park and protect the rights of the indigenous people whose existence is threatened by the oil exploitation.

Yasuní is a worldwide symbol – if we achieve to stop the oil exploitation in the Ecuadorian amazon, we are one step further towards saving the amazon, saving our climate, and creating a post-oil society in Ecuador and beyond.

Please vote and share this!

Posted by rogerhollander in Criminal Justice, Ecuador, Energy, Environment, Human Rights.

Tags: bianca jagger, chevron, cofan, Ecuador, ecuador oil, ecuadorian amazon, environment, environmental devastation, environmental lawsuit, Huaorani, human rights, kichwa, lewis kaplan, oil spill, oil-contaminated water, roger hollander, secoya, siona, texaco, toxic waste

And there comes a time when one must take a position that is neither safe nor politic, nor popular, but he must do it because conscience tells him it is right.” — Martin Luther King, Jr.

Ecosystemsin the Ecuadorian Amazon have been contaminated with by-products of oil extraction

Tomorrow, October 15, a landmark trial opens in federal court in New York City: Chevron Corp v. Steven Donziger et al., one of the world’s largest oil companies against the attorneys and advocates who represent the 30,000 “Lago Agrio Plaintiffs.” The case is the latest in a long and often tragic saga of the Ecuadorian victims struggle for justice.

I am writing this because I don’t want the real issue to be forgotten. The Ecuadorian communities are fighting for justice for the human rights violations and environmental crimes committed by Texaco between 1971 and 1992 in the Northern Ecuadorian Amazon. Since 1993 these Ecuadorian victims have been seeking relief in the largest environmental lawsuit in Latin America to date.

In 2003 I visited the affected communities in the Ecuadorian provinces of Orellana and Succumbios, and I have long supported them in their quest for justice.

Bianca Jagger by an oil pit, Ecuador, 2003I am not writing as an apologist of the legal team, nor am I condoning their behavior — but I feel the need to speak up on behalf of the Ecuadorian victims who may now never get the justice they deserve. It’s critical that Judge Lewis Kaplan, the media, and the public at large don’t lose sight of the real issue.

Bianca Jagger by an oil pit, Ecuador, 2003I am not writing as an apologist of the legal team, nor am I condoning their behavior — but I feel the need to speak up on behalf of the Ecuadorian victims who may now never get the justice they deserve. It’s critical that Judge Lewis Kaplan, the media, and the public at large don’t lose sight of the real issue.

The original case against Texaco (now Chevron) has been well documented.

Between 1971 and 1992, Texaco embarked upon reckless oil exploration, pumping 1.5 billion barrels of oil from Ecuador. Texaco carved more than 350 oil wells in a rainforest area roughly three times the size of Manhattan and dumped approximately 16.5 billion gallons of oil-contaminated water into unlined pits — one and a half times the amount spilled by the oil tanker Exxon Valdez. When Texaco left Ecuador in 1992, it left behind 916 unlined open toxic waste pits, some just a few feet from the homes of residents. Leeching of highly toxic wastewater byproducts of oil extraction from these pits contaminated the entire groundwater and ecosystem in one of the world’s most valuable rainforests. As there is no running water in the region families, including thousands of children, have no alternative but to drink, bathe, and cook with poisoned water from streams, rivers, lagoons and swamps that have been contaminated by Texaco.

U.S. states have laws requiring that pits have impermeable liners. Louisiana and Texas, two major oil-producing states, passed such laws in the 1930s. Texaco must have been aware of the dire consequences of leaving unlined pits exposed — they made a calculated decision, based on profit. The company saved an estimated $3 per barrel of oil produced by handling its toxic waste in Ecuador in ways that were unthinkable and illegal in the US. The cost to the human population is immeasurable. Ecosystems have been destroyed, diseases have proliferated, crops have been damaged, farm animals killed.

During my visits to the affected communities in 2003, I was appalled at the evidence of the consequences of direct exposure to these toxic waters. The suffering and environmental devastation I witnessed is not a fabrication, or a fiction. There is a toxic legacy left by Texaco for present and future generations.

In May 1995, three years after Texaco left Ecuador, the Republic of Ecuador and Texaco reached a settlement regarding Texaco’s obligations to clean up a percentage of the well sites roughly corresponding to its percentage ownership in the consortium that made money from the drilling. Ecuador’s state-owned oil company, PetroEcuador, was the 62.5 percent majority owner of that consortium from 1976 to 1992, so Texaco was required to clean up only a minority of the well sites. The settlement would later form part of Chevron’s claims that the case had been settled. It did not, however, extinguish the claims of individual third parties, or affect the rights of the communities affected by Texaco’s actions. Certainly the “clean up” undertaken by Texaco was limited and has made no material difference to the lives of the Ecuadorian communities.

Ecosystems contaminated by Texaco’s activities in Ecuador.

Ecosystems contaminated by Texaco’s activities in Ecuador.

The Texaco disaster culminated in the largest environmental lawsuit in Latin America to date; brought by 30,000 plaintiffs from the Ecuadorean Amazon. They filed a billion dollar class action against Texaco in New York. Texaco moved to dismiss the U.S. lawsuit on forum non conveniens grounds. In 2002 the court granted Texaco’s motion, and the case moved to Ecuador on the condition that the company stop using an expiration of the statute of limitations as a defence and that any judgment be enforceable in the U.S. Among the plaintiffs are five indigenous tribes, the Cofán, Siona, Secoya, Kichwa and Huaorani.

The Ecuadorian Amazon in the wake of Texaco.

Chevron acquired Texaco in 2001. Unlike the Exxon Valdez and the Deepwater Horizon accidents, where Exxon and BP, respectively, took some responsibility for their negligence, Chevron has successfully managed to move the case outside of the U.S. because it provided them with two options: to rig the judicial system in a foreign country, or to dodge its responsibility by not recognizing the validity of the verdict if it was not in their favor.

In February 2011, Judge Nicolas Zambrano issued a final verdict, ordering Chevron to pay $18.5 billion to the Ecuadorian plaintiffs. But as Chevron has no holdings in Ecuador, the plaintiffs have been unable to collect that judgement.

Chevron has paid more than $400 million to an army of lawyers to help the company avoid payment and spent over $100 million in lobbying firms to influence U.S. lawmakers and government officials to affect Ecuador’s trade with the U.S., and to discredit Ecuador, its government and legal system. Chevron has even been lobbying Congress and the U.S. Trade Representative not to renew Ecuador’s Most Favored Nation status, which expired on July 31, 2013.

Even prior to the 2011 Ecuadoran ruling, the law firm Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher, representing Chevron, was shifting the case physically, from Ecuador to New York, from pollution and human rights to attorney ethics.

Gibson Dunn won U.S. court orders forcing the makers of the feature documentary CRUDE to turn over 600 hours of raw footage on the Ecuadorean case in 2010. This footage apparently shows an attorney for the Ecuadorian communities, recounting how he has put pressure on Ecuadorian judges. Now Chevron has accused the attorney of fraud and racketeering — of attempting to obtain the settlement for his own personal benefit, and brought the civil lawsuit against the trial lawyers and consultants for the Ecuadorian plaintiffs.

Chevron brought three collateral actions against the Ecuador judgment in a New York federal court, all overseen by Judge Lewis Kaplan, who has a puzzling attitude toward the case. The Ecuadorians asked that Judge Kaplan be recused from the case in 2011. In their writ of Mandamus the Ecuadorians expressed their concern at the Judge’s language — referring to them as the “so-called Lago Agrio plaintiffs,” and in one written order, describes them as “a number of indigenous peoples said to reside in the Amazon rainforest.”

On Jan. 26, 2012, a three-judge panel of the 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that Judge Kaplan previously overstepped his authority when he tried to ban enforcement around the world of the $18.5 billion judgement against Chevron Inc. for environmental damage in Ecuador. But Chevron has retaliated.

Which brings us back to the suit that begins tomorrow, October 15, in a federal district court in New York, once again before Judge Kaplan. In order to avoid a trial by jury Chevron has dropped their claims for damages against the defendants. There is a massive imbalance of power and resources between the two sides. Unlike Chevron, the defense has scant resources — as demonstrated by this motion by Julio Gomez, which asks that the trial schedule reflect the fact that

My firm has no funds to hire an associate, a paralegal or even an assistant to help me through trial given the fact that I have insufficient funds to cover outstanding bills – much less fees going into trial. I have not even been able to contract the two assistants who aided me temporarily with the filing of Defendants’ draft pre-trial submissions in August.

Chevron has also subpoenaed nine years’ worth of email metadata — from September 2003 to 2012 — from 101 email accounts belonging to people with connections to the case. Data requested includes names, time stamps, and detailed location data and login info. Judge Kaplan granted this subpoena in September 2013. According to Mother Jones, this strays dangerously close to violation of First Amendment rights.

The Republic of Ecuador is also seeking leave to intervene to protect the confidentiality of privileged documents which appear to have made their way into Chevron’s suit without explanation.

The case of the Ecuadorians is being lost in a legal labyrinth. Avenues of legal recourse are being closed off, so that the victims have nowhere to turn.

The $18.5 billion judgement in favor of the Ecuadorian plaintiffs should have been historic, a landmark, a precedent for ending impunity for powerful multinational corporations in the developing world and achieving justice. It was a beacon of hope. But after 20 years of long, hard battle, I am beginning to have serious doubts as to whether the victims in Ecuador will ever be compensated.

The Ecuadorian communities were the victims of exploitation by a multinational corporation, Texaco. Their lives, and that of their children, are affected by the toxic waters that leaked into water sources on which they are dependent. This is the real issue, and it is a story that is all too common throughout the developing world. With their legal team on trial, who will pursue justice for the Ecuadorian plaintiffs now?

I appeal to Judge Kaplan, to the media, and to the public at large — please don’t forget what is at stake here. Don’t let this legal imbroglio eclipse the issues which are really at the heart of this case: human rights, justice and environmental protection.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 License

Bianca Jagger is a prominent international human rights and climate change advocate. She is the Founder and Chair of the Bianca Jagger Human Rights Foundation, Council of Europe Goodwill Ambassador, Member of the Executive Director’s Leadership Council of Amnesty International USA, Trustee of the Amazon Charitable Trust, and on the advisory board of the Creative Coalition. For over 30 years, Bianca Jagger has campaigned for human rights, social and economic justice and environmental protection throughout the world.

Posted by rogerhollander in Ecuador, Foreign Policy, Human Rights, Imperialism, Latin America.

Tags: ., assange, economic blackmail, Ecuador, ecuador asylum, ecuador trade, ecuadorian government, edward snowden, human rights, Latin America, Rafael Correa, robert menendez, roger hollander, trade preferences, whistle blower, wikeleaks

Published on Thursday, June 27, 2013 by Common Dreams

Vowing not to be bullied, nation cancels trade pact preemptively and offers US human rights training

– Jon Queally, staff writer

30-year-old Edward Snowden, a former National Security Agency contractor who embarrassed the US government by revealing details of vast Internet and phone surveillance programs, has requested asylum from Ecuador.(Photo: scmp.com)The clear message from the Ecuadorean government on Thursday is that it would not be bullied or ‘blackmailed’ by the US government over the possible asylum of Edward Snowden.

At a government press conference held in Quito, officials said the US was employing international economic “blackmail” in its attempts to obtain NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden, but that such threats would not work.

Snowden, who remains inside an airport terminal in Russia, has become a flashpoint between Ecuador and the US after confirmation that the 30 year-old intelligence contractor has sought asylum in the Latin American country.

Ecuador indicated its offer of ‘human rights assistance’ the US could be used to help address its recent problem with torture, illegal executions, and the attacks on the privacy of its citizens.